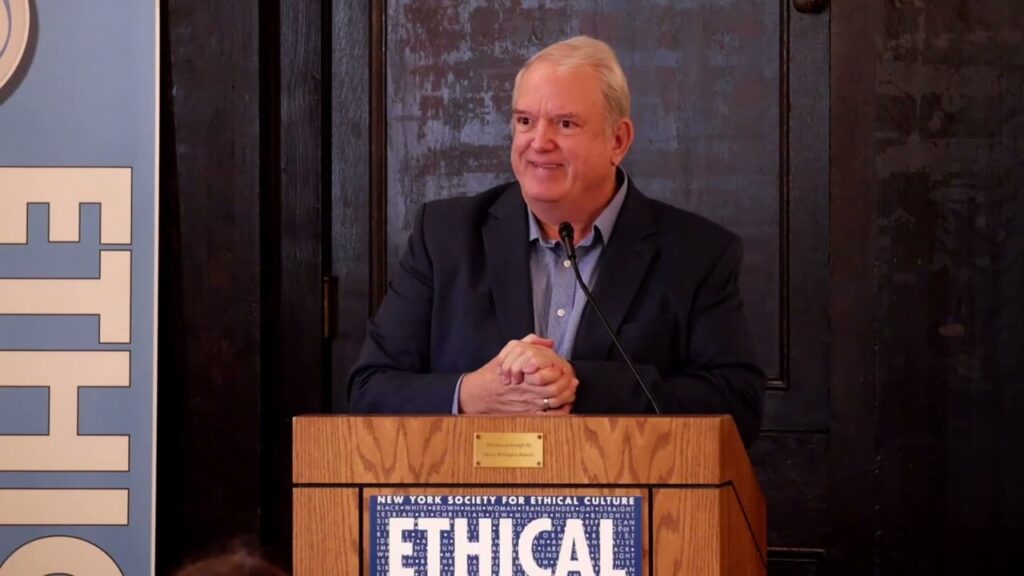

At yesterday’s Sunday Platform in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, Leader Dr. Nori Rost examined the personal and philosophical relationship between Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, the profound influence they had on one another, and what it can teach us about fighting against racism in our time:

•••

This weekend we celebrate one of the greatest Civil Rights leaders of all times. Someone who changed the face of our nation for the good. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would have been 94 years old today if James Earl Ray had not gunned him down on April 4, 1968 in Memphis, TN.

Recently Barbara Walters died and I reflected on how she was born the same year as Dr. King and Anne Frank. It is interesting to see how their lives played out based on the race, where they lived and their culture. One died as a teenager in a Nazi concentration camp; one was gunned down in Memphis, TN at the age of 39; one was a trailblazer for women in the media and lived to the old age of 93. Each changed the world, only one lived to old age, but each lived fully into the lives they were given.

In 1986, this federal holiday was created to commemorate Dr. King’s life of non-violent justice-seeking. But there was another Black leader who had an equal impact on our nation who history doesn’t remember so kindly.

Malcolm X was born May 19, 1925, as Malcolm Little. Whereas Martin was known for his staunch non-violent civil disobedience tactics, Malcolm was known for his blunt calling out of white complicity in keeping people of color oppressed, and his gospel of separation from white society.

The press loved to portray the two men as being diametrically opposed and enemies of one another, but in reality, they were fond of one another, according to theologian James Cone, who wrote of the two in his book, Martin and Malcolm and America: A Dream or A Nightmare?

Although their tactics were different they both saw each other as fighting for the same thing: freedom for African Americans. And though their tactics were different, they both were coming from African American protest traditions.

Martin was speaking from the integration perspective, and Malcolm from the nationalist/African identity perspective. Each of these perspectives have their roots in the post slavery era. Frederick Douglass, for example was a staunch integrationist, and Nat Turner, a staunch nationalist.

So, Martin and Malcolm came from a long line of African Americans before them advocating freedom for Blacks in different ways.

History often wants to paint Malcolm X as a race-baiter, a troublemaker whose violent past never left him. But in reality both he and Martin Luther King were products of their environments.

King was born and raised in a loving, stable home in the south where legal racism was evident everywhere.

Malcolm X was raised in Lansing, MI where his father was killed when Malcolm was six years old. His widowed mom struggled to raise the seven children on her own and Malcolm took to stealing food to help the family.

He lived in the north where there weren’t signs saying whites only, but where the institutionalized racism kept the African American communities in ghettoes of poverty.

He saw the indifferent brutal injustice of police brutality.

Dr. King looked to his deeply held Christian values that taught all people were children of God loved equally by God. Based on this he firmly believed that white Christians would see the injustice of racism as they practiced their faith, and of course, would support this Southern Freedom movement.

And we see that today, too, don’t we? We even may have said the same thing. Surely, those who are Christians will reject the atrocities coming out of the White House when Trump was in office because they go so deeply against the grain of the Christian faith. Surely, they won’t vote for him in 2020. And like King, sadly we too are faced with the realization that many white Christians prefer the power of their privilege over the teachings of Jesus.

But King persisted in his integrationist approach for most of his life.

Malcolm X, living off his wits, drug running, being a pimp, getting busted for a robbery ring that landed him in jail with an 8-10 year prison sentence, didn’t have that Christian base.

In prison he learned of a new branch of Islam called the Black Muslims led by Elijah Muhammed who claimed to be the anointed leader of Allah. Having seen how African Americans were rendered powerless in the north this religion appealed to Malcolm X and he became Elijah’s most devoted disciple.

He used his time in prison to read and educate himself; he spent his time in the prison library and when he was released, he became a prophet of nationalism, of proclaiming Blacks could only be free if they lived separately from whites.

He said he couldn’t claim the title American because he didn’t have the freedoms and rights of one. He said, “If I sit at the table where you’re eating, and I don’t have any food that doesn’t make me a diner.”

Whereas Martin called on the benevolent justice of God who loved all, and his dream included black and white children playing together, Malcolm said very clearly that whites were the devils taking humanity away from people of color.

Martin was surprised by the white’s non-involvement; Malcolm expected nothing more from whites.

But each was speaking in a language that could be understood and made sense to their audiences.

Martin had been speaking for Southern Blacks—where they couldn’t sit at counter; Malcolm had been speaking for ghettoized Northern blacks who were kept in cycle of poverty and couldn’t afford to sit at counter.

It wasn’t a case of who was right or wrong. Though the media tried to portray Martin as a kinder, gentler integrationist, and Malcolm as a nationalist to be feared, actually they each influenced the other profoundly.

In 1964, Malcolm X broke with the Black Muslims after learning of Elijah Muhammed’s inability to keep his pants up. And as he left that restrictive movement, he began to open up more, to move more towards Martin’s point of view.

In his Bullet or Ballet speech in 1964 he said (speaking of Martin) “I’m not for separation, you’re not for integration What you and I are for is freedom. We’ve both got the same objective, we’ve just got different ways of getting at it.”

In the 11 months following his independence from Black Muslims he said repeatedly, “Dr. King wants the same thing I want—Freedom.”

Who knows where his ideology would have evolved if he had lived longer? Sadly, he was gunned down by three members of the Black Muslims on February 21, 1965, just short of a year after leaving that sect.

But Martin also was evolving more towards Malcolm’s point of view, too. The Watts riot on August 11, 1965, which left 34 dead and 4000 arrested, with entire city blocks burned to the ground caught Dr. King and the Southern Freedom movement completely off guard.

Following that King began to see that “there are literally two Americas: One beautiful, rich and primarily white and the other ugly, poor, and disproportionately black.”

The other America as he began to call it helped him to understand something of the world that created Malcolm X.

He said to his advisor, gay, Black Quaker, Bayard Rustin, “I’ve worked to get these people the right to eat hamburgers, and now I’ve got to do something to help them get the money to buy them,” He realized that formal equality didn’t mean material conditions of black Americans would change. He moved more to a separatist point of view.

Each saw the other’s point more clearly.

Sadly, Martin and Malcolm, although referring to the other often in interviews, only met once.

At the Capitol where the Voting Rights Act was being debated, they had each held press conferences. As Dr. King was coming out of one, Malcolm approached him; the entire exchange only lasted a moment.

“Well, Malcolm, good to see you,”

“Good to see you, Martin.”

They walked down the hall as cameras clicked.

It’s a haunting moment, a sense of unrealized potential that leaves us wondering what could the two of them have accomplished had they both lived long enough to complete their evolution. What a force for justice they could have been.

One has a federal holiday, one does not. But they both changed our world for good.

What we can learn from this in today’s movements (not moments), in the Women’s Marches happening around the country next Sunday, and the immigration issues that are always with us, and the Black Lives Matter Movement is that those of us who are white must acknowledge our complicity. How we are like the religious folks in King’s day who, rather than standing up with him, either condemned or did nothing.

Our white privilege making it easy to turn a blind eye. We also all need to see how our classism impacts us, whatever race we are.

We need to take time to seriously examine our own assumptions about why we strive for justice—or even what we consider justice to be–and how that stems from our own class and race and place in this world, just as it did for Barbara Walters, and Anne Frank, and Martin Luther King, Jr.

If we are to truly honor the lives of these two men, we need to continue the work they began, both reaching across the table when appropriate, and bluntly calling out when necessary.

And we need to be open to evolution in our own lives. We need to be willing to have our own cages rattled.

Next month I am beginning a new experiment here: Ethics Unplugged, an alternative midweek platform that we’re collaboratively creating.

It will be much different than what we’ve come to expect from a Sunday morning platform. We will unapologetically create content that lifts up the voices and experiences of the historically underserved.

And when I say historically underserved, of course I mean in our nation, but I also mean in our Ethical Societies. The reality is that The Society for Ethical Culture was founded by a white, cis-gendered, heterosexual man of privilege, and that’s who it was designed for.

And we like it. We like being with folks like us, after all. And we like hearing great speakers talk about issues of the day.

There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s important for us to be made aware of issues we might not know anything about if not for speakers at the Sunday Platform.

That will continue.

But if we are to be relevant, we must expand our identity to include the historically marginalized.

If you’re wondering if you’re in a group that’s historically marginalized, here’s how you can know: If you have ever known that the election of a person to the office of President or Governor might impact your basic human rights will be affected, you’re a part of a historically marginalized group. If you vote for a candidate based on issues but know that whoever gets elected, you’re pretty much protected, that means you’re not.

Women got that loud and clear this past May when the politically charged conservative Justices of the US Supreme Court overturned the basic human right of having agency over our own bodies and access to abortions. That was because someone in power appointed people to serve on that court.

Queer people get that when their ability to marry legally was also threatened by that same court, although thankfully the Marriage Protection Act was passed to protect marriage equality for queer people as well as interracial marriages; those were all on the chopping block.

Black and Brown people get that when states where conservative Republicans won passed voting restriction laws designed to make it harder for them to vote.

We live in New York City, one of the most diverse cities in our nation. There are more than 200 languages spoken by the citizens of our city. As much as we love our traditional Sunday Platform, it does not speak to the vast majority of cultures in our fair town.

That is not an indictment against you or me. It’s an awareness that we need to expand our reach.

Don’t we want to be the place in Manhattan where folx of all races, ethnicities and cultures can find an ethical home that speaks in a language they understand? Don’t we want to be that place? I want to be that place. And thankfully, it doesn’t cost us anything, personally, to expand that reach.

We do live in two Americas. Actually, more than that, as Malcolm and Martin discovered. We are called as Ethical Culturists, not to bring people into our America, into Felix Adler’s America, but to create a place where all people can live into the fullness of their lives; to demand that our America expands its reach to all people; to create a table where there is room for everyone:

Regardless of beliefs.

Regardless of race.

Regardless of gender identity.

Regardless of age.

Regardless of sexual orientation.

Regardless of relationship status.

Regardless of income.

Regardless of ability to be fully welcomed and seated at the table; to feast at the banquet and not be left out as Malcolm felt. To be able to say I am a diner at the Ethical Culture Society, and I am deeply satisfying, rich food for thought.

And so, I want to say I know it’s scary for some of you. This change seems scary. It’s not an indictment against how we are as Ethical Society, it’s an expansion of it.

I’m proud of you for saying yes to taking this step. I’m proud of you for saying yes to change, to diversity, to exploring the edges of our faith, our faith in humankind.

At the end of the day, that’s what Martin and Malcolm had: faith in humankind to do better.

As we celebrate them both today, I’m so grateful for this Ethical Society, the fine people here, and on Zoom, I’m so grateful that we are saying yes to the faith, too. May it be so.

___________

Cone, J. H. (2012). Martin and Malcolm and America – A Dream or a Nightmare?. Orbis Books (USA)

About Leader Dr. Nori Rost

Dr. Nori Rost is the acting Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture. Prior to that, she served as the settled minister of All Souls Unitarian Universalist Church in Colorado Springs, CO for 13 years. She previously was a minister in Metropolitan Community Churches (a queer Christian denomination) for 20 years before outgrowing the Christian faith.

She is passionate about social justice and has been involved in social rights activism since she was 17. She is an outspoken advocate for justice and equity and has received numerous awards and recognition for her work.

Nori holds a Master of Divinity from Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado, and a Doctor of Ministry from the Episcopal Divinity School in Cambridge, Massachusetts. In addition, she holds a Certificate for Spiritual Direction from the Benet Hill Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado and is also a Certified Life Mastery Consultant with Brave Thinking Institute.

Monthly Collection: M.K. Gandhi Institute for Nonviolence

Sunday Platform is our most important and long-standing community event. These gatherings educate, stimulate personal growth, inspire reflection and action, and strengthen our community. Sunday meetings begin with music, followed by greetings and a talk given by a Society Leader, member, or guest. Platforms cover a variety of topics that reflect current events, pressing social issues, and Humanist philosophy. Each Sunday meeting is followed by a luncheon and social hour.

To watch previous Sunday Platforms, visit our Videos page and YouTube channel.