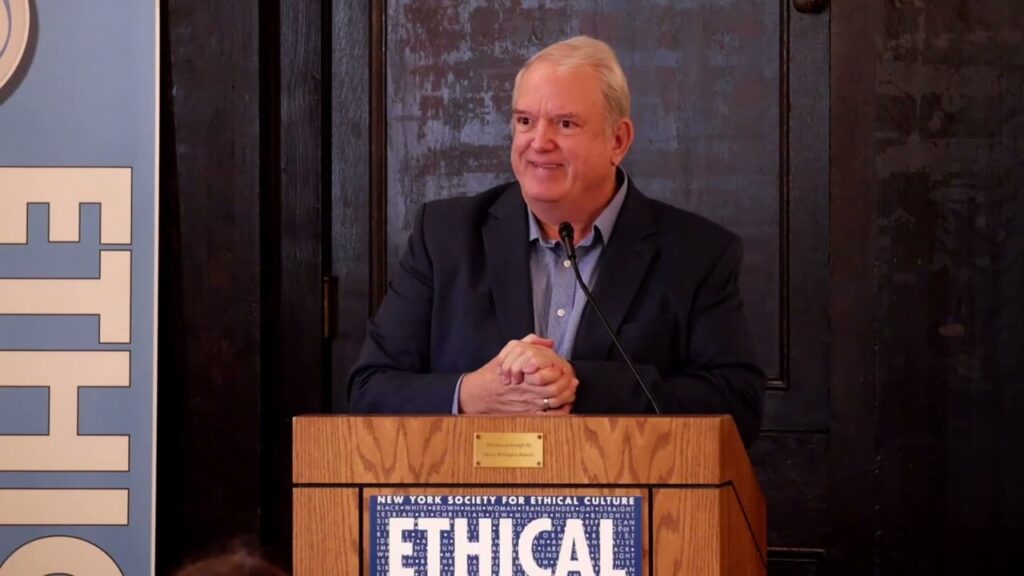

One day a student asked me to give the class I was teaching a blessing. I was taken aback, stuck on that word: blessing. The class was called “Humanist Spirituality,” and we were in a classroom at Union Theological Seminary. My students were candidates in the Master of Divinity program, and we were discussing a passage in an excellent book by philosopher Robert C. Solomon entitled Spirituality for the Skeptic: The Thoughtful Love of Life.

I often teach classes on humanism to self-identified humanists; this was the first time my students were theists. I had suggested the course to the seminary because I suspected that I would find some “not-yet-unidentified as” humanists there. What I found were “humanistic theists” or people who had a transcendental, not a supernatural, sense of deity. Throughout the semester, we compared theology and philosophy, shared our own experiences, and sought a common language.

Some words are rejected as irrational by (or fraught with emotional weight for) humanists. Words like sacred and holy, spirituality and blessing can conjure up an otherworldliness that we eschew. Life in this natural world is enough. It holds enough wonder and awe without belief in an afterlife or the supernatural. But these words can also describe deeply human experiences, ones of connection to nature and other people. Solomon writes “that if spirituality means anything it means thoughtfulness. . . [and], like philosophy, involves those questions that have no ultimate answers, no matter how desperately our various doctrines and dogmas try to provide them.”

One day we were discussing a quotation from Albert Camus’s novel, The Stranger: “I opened my heart to the benign indifference of the universe.” For me, this existentialist philosopher, who confronted the Absurd and also wrote, “I know of only one duty, and that is to love,” is a humanist “saint.” I find in his work a freedom and humor that comfort me. This was, however, not the case for one of my students whose theism was expressed in a purpose to the universe and a special place for humans.

And this brings me back to her request for a blessing. If the universe is indifferent, what does it mean to feel gratitude for one’s life? Is it a blessing to be alive? Should we count our blessings – and bless others?

I thought about the phrase I recited as a child in the confessional box at St. Anne’s Church: “Bless me, Father, for I have sinned.” It is a request to listen and accept the litany of sins to follow. I also remembered Irving Berlin’s song, “Count Your Blessings,” which he used in the 1954 movie “White Christmas.” He credited his doctor with suggesting that he try “counting his blessings” as a way to deal with his insomnia. The final lyrics are: “If you’re worried and you can’t sleep/ Just count your blessings instead of sheep/ And you’ll fall asleep counting your blessings.”

I decided to express gratitude to my students. They challenged me in ways that I hadn’t expected, and I had learned as much as I had taught. They trusted me and each other enough to share their personal experiences. They were a blessing. “OK,” she persisted, “but will you bless us?” Had I not been a blessing to them, too, I wondered? And then I really listened and understood. “I bless the journeys that you have undertaken to find purpose in your lives and to engage others with compassion.” It worked, to judge by the nods and smiles I received.

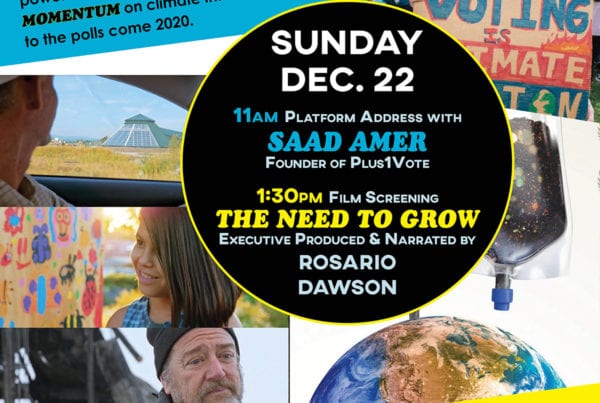

“Blessing” is variously defined as approval, encouragement, a thing conducive to happiness, and a grace said before a meal. To “bless” is to consecrate by religious rite, endow favor, or invoke a wish for good health. It seems to me that we would do well to both count our blessings and bless others. There is much work ahead of us this year to further our social justice mission. Let us also remember that we are blessed with a history of activism that inspires us, a meeting house that holds and supports us, and a community of members that strive to be their best ethical selves.

(By the way, next semester I’m teaching a class at Union on humanist ceremonies.)