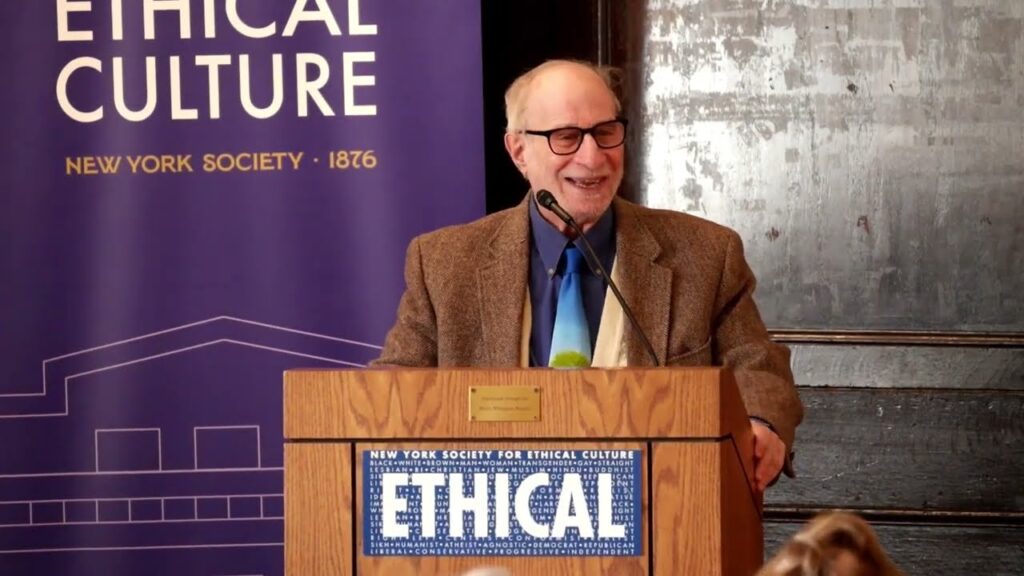

By Dr. Joseph Chuman, Leader

Ethical Culture was founded on May 15, 1876, and I’ve been asked this month to write on a topic relevant to our Founder’s Day. But, before speaking of our past, I feel compelled to address the present.

As I write this article, the trial of George Floyd’s murderer is taking place. The nature of the crime is such that we cannot turn away. The reality is stark; for more than nine minutes, a police officer, with total control over his subject, literally squeezed the life out of George Floyd as he lay prone on the pavement with hands cuffed behind him, pleading for his life.

In that horrible event is the much broader question of humanity. George Floyd’s murder at the hands of a white police officer is representative of the dehumanization of Black people in America that extends back more than 400 years. The pervasive history and reality of racism come together graphically, with indisputable clarity, in this one event. It is a murder with implications much greater than the discrete crime alone.

But the even larger question is why some people count and others count less. It is this disparity that has enabled history’s worst crimes, among them slavery, genocide, and the torture of human beings. It also allows and justifies the pervasive oppression, political and economic, of one class of people over another.

How can we ensure that human beings count? How can we safeguard the humanity of women and men, especially those who are different from us?

The answers as to how and why are complex, but they need to compel our greatest attention. In my opinion, the answers relate to the ability to view, appreciate, and ultimately embrace the humanity of people who are different from ourselves. The inability to appreciate the humanity of “the other” has enabled racism to flourish, not only here, but virtually in every society in which minorities are found, which means virtually all societies.

The most evident and painful exemplification of this phenomenon is manifest in the reality of genocide, the planned and orchestrated annihilation of thousands, tens of thousands, and millions of human beings. The progressive dehumanization of “the other” is a necessary step along the way toward wholesale slaughter. The Nazis employed medical metaphors. The Jews were a disease infecting the Aryan body and needed to be excised—a plague, vermin, to be exterminated. The Hutus referred to their Tutsi victims as “cockroaches” before preceding to slice to death 800,000 in a hundred days with knives and machetes. The Serbian genocidaires assessed their Bosnian victims in the Balkan wars of the 1990s as “Muslims” and not as human beings, and proceeded to murder and rape them without conscience.

How does one know the human from the non-human? Since at least the time of Aristotle, the criterion in the West was the attribute of impersonal reason. In the thought of white, European-originated males, Blacks lacked a capacity for abstract thought and were more like perpetual children than themselves. Human beings? Perhaps. But of a lesser type, sufficiently deficient to justify enslaving them. Women, also further down on the rationality spectrum, relegation to the domestic sphere and a status of subordination were their due.

There were other criteria commensurate with humanity. Until modern times and the emergence of science, which eroded the authority of religion, most believed that humanity resulted in human beings, who are created “in the image of God.” We are not God, but a reflection of the divine, and hence unique in all of nature. We thereby possess a soul, which other creatures lack, and in our soulfulness resides our humanity

Felix Adler was a modern who accepted the deliverances of science and, with that, the acids that stripped away the truths of religion. But Adler also lived in an urban environment in which the masses suffered under the excesses of the Industrial Revolution—pervasive poverty; wage slavery as workers who toiled at their machines in dangerous factories; teeming, overcrowded tenements; substandard education— in other words, conditions that were dehumanizing.

Unable to look to the religions to find our humanity, the question that Adler confronted—and it was urgent—is how can we ensure that human beings count? How can we safeguard the humanity of women and men, especially those who are different from us?

This, I submit, is the question that gave rise to Ethical Culture 145 years ago. It was the central question that preoccupied Adler. And I contend, given the endurance of racism, given the realities of war, mass slaughter, and human cruelty, it remains our question that continues to call out for an answer. How can we respond? How can we vouchsafe humanity?