During the first week of January 1909, three people met in a small room of a New York City apartment and decided that on the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birthday they would issue a call for a national conference on “The Negro question.” They were Ethical Culture Leader Dr. Henry Moskowitz, Unitarian Mary White Ovington and William English Walling, a reporter who covered the race riots the summer before in Lincoln’s home of Springfield, Illinois.

For two days in the summer of 1908, a mob of white people, including some of Springfield’s “best citizens,” raged against the African-Americans of their city. As they killed and wounded them, and destroyed their homes and businesses, these racists shouted, “Lincoln freed you. Now we’ll show you where you belong!” There were other race riots throughout the country, but no one described the atrocities as vividly as Walling did in his article, “Race War in the North.” He also asked an important question: “Yet who realizes the seriousness of the situation, and what large and powerful body of citizens is ready to come to their aid?” After reading Walling’s article, Ovington, who for years had been studying the housing conditions, health, and work opportunities of African-Americans in New York City, and lived in one of their neighborhood tenements, wrote to him: “The spirit of the abolitionists must be revived.”

The trio, having decided to call for a conference, reached out to Oswald Garrison Villard, president of the NY Evening Post, grandson of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, and member of the New York Society for Ethical Culture. It was he who drafted the “Call for the Lincoln Emancipation Conference to Discuss Means for Securing Political and Civil Equality for the Negro” and widely disseminated it. It begins with this challenge:

“The celebration of the centennial of the birth of Abraham Lincoln widespread and grateful as it may be, will fail to justify itself if it takes no note and makes no recognition of the colored men and women to whom the great emancipator labored to assure freedom. Besides a day of rejoicing, Lincoln’s birthday in 1909 should be one of taking stock of the nation’s progress since

1865. How far has it lived up to the obligations imposed upon it by the Emancipation Proclamation? How far has it gone in assuring to each and every citizen, irrespective of color, the equality of opportunity and equality before the law, which underlie our American institutions and are guaranteed by the Constitution?”

Villard catalogued the gross injustices African-Americans continued to endure since the Emancipation Proclamation. The Call ends, as if in anticipation of what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. would say almost 60 years later – “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” – with these words:

“Silence under these conditions means tacit approval. . . Discrimination once permitted cannot be bridled; recent history in the South shows that in forging chains for the negroes, the white voters are forging chains for themselves. . . Hence we call upon all the believers in democracy to join in a national conference for the discussion of present evils, the voicing of protests, and the renewal of the struggle for civil and political liberty.”

Among the 53 signers were four Ethical Culture Leaders: Jane Addams and Walter Salter from Chicago and John Lovejoy Elliott and Henry Moskowitz from New York. The proposed conference was opened on the evening of May 30, 1909 with an informal reception at the Henry Street Settlement hosted by Lillian D. Wald, and deliberations began the next day at Cooper Union. According to Mary White Ovington, “These men and women, engaged in religious, social and educational work, for the first time met the Negro who demands, not a pittance, but his full rights in the commonwealth. . . They did not want to leave the meeting.”

Out of this first conference was formed a committee that, by the end of the year, held four mass meetings, distributed thousands of pamphlets and grew to hundreds in membership. At a second conference in May 1910, a permanent body known as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People was organized. The most important work of this conference was the appointment of W.E.B. DuBois, leader of the Niagara Movement formed in 1905, to the position of Director of Publicity and Research. Twenty years later, DuBois wrote to Walling about the “cousins” who together founded a mighty movement for civil rights.

As we look back upon our history, let us again stalwartly take up the challenge of “assuring to each and every citizen, irrespective of color, the equality of opportunity and equality before the law, which underlie our American institutions and are guaranteed by the Constitution.” We are, tragically, again facing a moment when the rights of our “cousins” are being attacked. We must not be silent! Take action today by joining a local branch of the NAACP (http://www.naacp.org/) and the American Civil Liberties Union (https://www.aclu.org/), another organization founded by Ethical Culture.

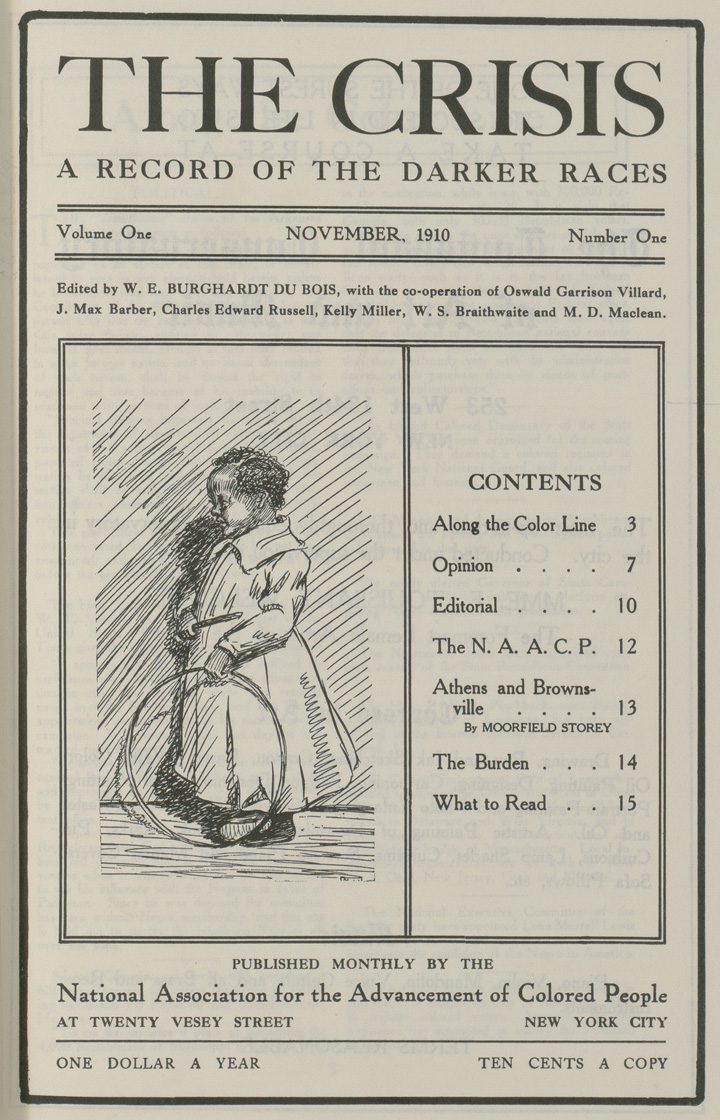

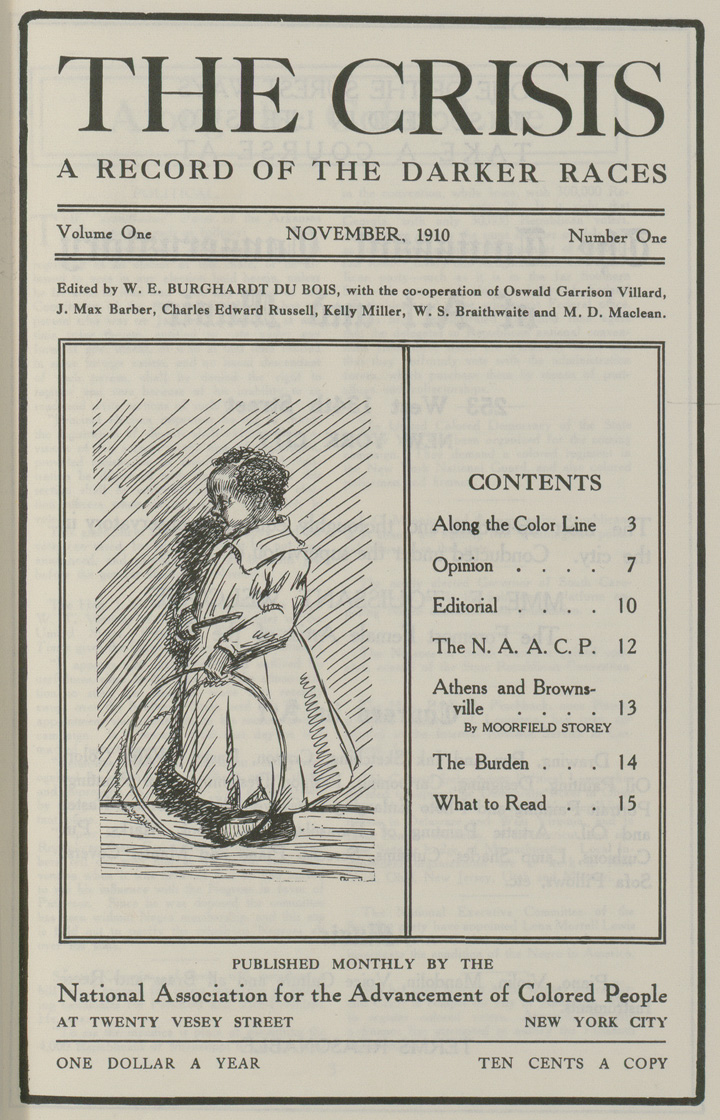

The very first image of The Crisis, the official journal of the NAACP.