I never met my favorite Ethical Culture Leader because he died in 1942, years before I was born. John Lovejoy Elliott, founder of Hudson Guild, a settlement house in Chelsea, was known first and foremost as a good neighbor. I keep a copy of “Unconquerable Spirit: Selections from Addresses and Writings” on my nightstand. In the foreword, his protégé Algernon Black wrote, “To the thousands who knew him, his nature and gifts and purposes are a testament to the miracle of the human personality. He loved people and undertook to help people live. . . He sought a religion deeper and truer than any theology. The lives of the people around him were a sacred revelation.”

In this last month before I retire as congregational Leader of the New York Society for Ethical Culture, I have sought counsel from Dr. Elliott, starting with his definition of religion as “a sense of connectedness,” declaring that “the spirit of religion is a fire passed from life to life, not by instruction, but by kindling.” Human relationships were important and precious to him, and he believed that the Ethical Movement had “in some degree” succeeded, “through its social, human message,” to express a religion of democracy. “I am filled with the sense of wonder and awe,” he wrote, “in the presence of the spiritual nature as it manifests itself in the daily lives of men and women.”

Dr. Elliott taught ethics in the Ethical Culture Fieldston Schools. One of his students recalled him beginning a class by asking if anyone knew the name of their postal carrier. He and his friends laughed nervously, wondering if Dr. Elliott could be serious. He was. A postal carrier plays an important role in society: keeping people connected. It reminds me of the Sesame Street song, “Who Are the People in Your Neighborhood?” that includes a litany of jobs in addition to postal carrier: firefighter, teacher, baker, doctor, bus driver, and, for my favorite character Oscar the Grouch, trash collector. My children and I sang these lines when we walked around our neighborhood years ago: “They’re the people that you meet when you’re walking down the street. They’re the people that you meet each day.”

Elliott cared about neighborliness: “It is a mutuality, reciprocal relations between people, and not only just from one to the other, but mutuality in all the essential ways of living. That, I believe, is the deepest thing in all our lives.”

I began my career as a professional Leader at the NY Society interning with then Leader Khoren Arisian on the fateful day of September 11, 2001. Throngs of people came through our doors that year and attended Sunday platforms in a crowded auditorium. They sought understanding and inspiration. It was a challenging experience for all of us. While Khoren spoke eloquently from the stage, I was given responsibility for pastoral care and sought ways to make our meeting house a safe and comforting space.

I remember one day arranging chairs in a circle in Ceremonial Hall. One of the men from the maintenance staff rushed over and said, “I’ll do that. Just tell me where you want them.” Having been raised in a small Catholic parish and raising my children in the even smaller Brooklyn Society for Ethical Culture, I was accustomed to setting out chairs, emptying wastebaskets, and bringing food for potluck dinners. I felt uncomfortable telling someone else to do something that I could easily do myself. “It’s my job,” he explained. “How about this?” I asked. “I’m not sure yet how I want this room set up. How about we do it together?” That was how I met Leonardo Gibson, who is now Facilities Manager. Years later, when I returned from six years as Leader of the Ethical Humanist Society of Long Island, Leonardo graciously read the part of Frederick Douglass to my Susan B. Anthony in a play I wrote for a Sunday platform.

Like John Lovejoy Elliott, I wonder if our members know the names of our staff, professional and maintenance, who support our community in myriad ways, and thank them. I have observed these dedicated people behave as good neighbors, sometimes under difficult circumstances, to everyone who enters our meeting house. They are often the first people a visitor sees, before coming to a Sunday platform or Newcomer Reception, and they make us look very good.

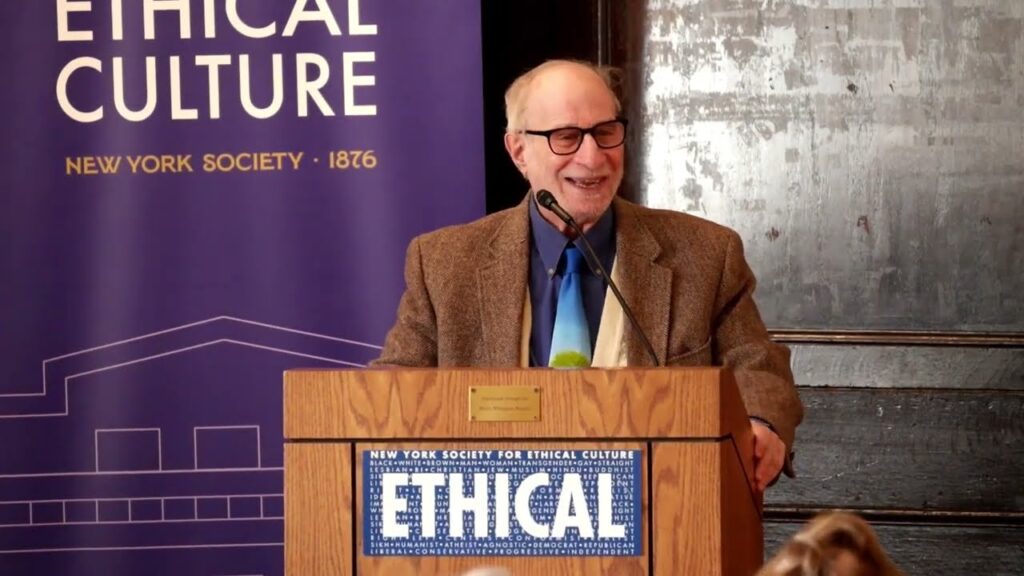

I have included a photo of most of our staff taken at Carmine’s on August 7 at my retirement lunch. Their names and the names of those who couldn’t join us are in the caption. I hope you will join me in thanking them for taking such good care of us.

John Lovejoy Elliott’s last words were “The only things I have found worth living for, and working for, and dying for, are love and friendship.” Let us all say “Amen!”