Since 1976, every United States president has officially designated February as Black History Month. Here’s hoping President Trump does, too. He, more than any other president since 1976, needs to learn the lessons of Black History Month. A case in point: During the presidential campaign, Trump said there had “never been a worse time to be a black person” in America. President Obama urged him to visit the National Museum of African American History and Culture (https://nmaahc.si.edu/) to brush up on his history. Trump seemed to have “missed that whole civics lesson about slavery and Jim Crow,” he said in a September speech at the Congressional Caucus Foundation in Washington, DC. “We’ve got a museum for him to visit, so he can tune in. We will educate him.” Sadly, Trump cancelled his plans to visit the museum on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. One wonders whether he did so because civil rights leader John Lewis, who chose not to attend his inauguration and questions his legitimacy as president, championed the creation of this museum and is featured in many of its exhibits.

In her memoir, Negroland, Margo Jefferson quotes her mother, who, in the 1950’s, was worried that her young daughters were “being naturalized into white culture.” “When I was your age,” she said, “we celebrated Negro History Week. The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History was founded by Carter G. Woodson right here in Chicago. We read The Crisis [official magazine of the NAACP]. We were so proud when we sang “Lift Every Voice and Sing’ at assemblies and church programs.” Jefferson writes, “From that day forward Mother began her own cultural enrichment course with evening and weekend contributions from Daddy.”

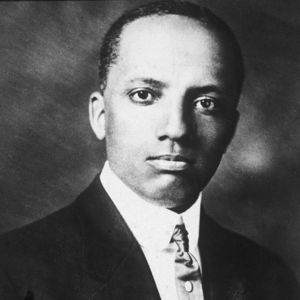

Black History Month grew out of Negro History Week, founded by noted historian Carter G. Woodson and launched in 1926 in the second week of February between the birthdays of Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. Woodson also founded the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History (ASALH) in 1915 and the Journal of Negro History in 1916. A prolific writer about the contributions of African-Americans, his best-known work is The Miseducation of the Negro, published in 1933. It focused on the Western indoctrination system and African-American self-empowerment.

Born to former slaves in 1875 in Buckingham County, Virginia, Woodson worked in mines and quarries until the age of 20, received his high school diploma at the age of 22 and a master’s degree in history from the University of Chicago. In 1912, Woodson received a doctorate in history from Harvard, but was unable to land a teaching post there because Harvard wasn’t hiring black professors. He taught instead at Howard University, one of the nation’s leading black educational institution.

Woodson spent his life investigating, documenting and publishing African-American history. He died suddenly of a heart attack on April 3, 1950 in Washington, DC, before realizing his ambition of publishing the six-volume Encyclopedia Africana.

The theme for 2017’s Black History month, selected by ASALH, is “The Crisis in Black Education,” a tribute to its founder. It focuses on the crucial role of education and recalls Woodson’s words: “If you teach the Negro that he has accomplished as much good as any other race he will aspire to equality and justice without regard to race.”

The crisis, according to ASALH, “first began in the days of slavery when it was unlawful for slaves to learn to read and write. . . [C]ontinuing today, the crisis in black education has grown significantly in urban neighborhoods where public schools lack resources, endure overcrowding, exhibit a racial achievement gap, and confront policies that fail to deliver substantive opportunities.”

I am finishing this column on Inauguration Day and will travel early tomorrow morning to Washington, DC to march for all that I hold dear about our nation. That includes Black History Month and the lessons we still have to learn.