Re-posted from Leader Joe Chuman’s Substack, Beyond Appearances.

Note: Below is a review of the book “Moving the Bar,” the autobiography of the radical attorney, Michael Ratner. Michael died in 2016, and the book was completed by two friends. Michael Smith served on the Board of Directors of the Center for Constitutional Rights, of which Michael Ratner was president. Zachary Sklar is a journalist, screenwriter, and editor who co-wrote the film JFK with Oliver Stone. He was also executive editor of the Nation and taught for many years at the Columbia School of Journalism.

I had the privilege of interviewing Messrs. Smith and Sklar on the book under the aegis of the Puffin Cultural Forum. Here is the link to the YouTube video.

_____________________________

“Moving the Bar: My Life as a Radical Lawyer,” is the autobiography of Michael Ratner, who exemplified a class of left-wing attorneys inspired by a relentless passion to combat injustice. Ratner, throughout his distinguished career, was as highly principled as he was devoted to the struggle. But unlike many dedicated to political causes, he also preserved a very human side.

His career extended into the current century, but was forged out of the ferment of the 1960s. It was a volatile and transitional era, and as I read his story I found myself in familiar territory. Many of the people Michael Ratner worked with crossed my path as well.

The 60s – when I reflect on those days, I recall a verse from William Wordsworth which has long gripped my imagination: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive. But to be young was very heaven!” Wordsworth penned that line in “The Prelude,” his magisterial autobiographical poem. As a student, Wordsworth spent his college years in Paris and was enthralled with the French Revolution, which he witnessed firsthand.

I reflect on Wordsworth’s nostalgic line when I think back on my own youth and my politically coming of age in the 1960s. It was a tumultuous and exhilarating time when many thought we were making the world anew. It was to be a rebirth that inspired talk of “struggle,” of bringing down “the establishment,” of undoing “oppression,” all conjoined within the argot of “revolution.” Like revolutions of the past, it would emerge out of the matrix of violence, and the 60s saw much violence– urban riots, assassinations, sit-ins, demonstrations, and days of rage, fueled by anger on the brink of disorder. Much came from the government side: police brutality waged against civil rights protesters, the killing of Black Panthers and students at Kent State, the drumbeat of the Vietnam War grinding on in the background. Martin Luther King, defending bringing non-violent protest to the streets, eloquently declared that progressive change, nevertheless, often requires the tension of conflict. And there was much.

In parallel with the activity of the street, there was the employment of the courts. It was the time of iconic jurists. There were giants in the earth in those days. The Warren Supreme Court, the most progressive in American history, was comprised of such luminaries as William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, William Brennan, and Thurgood Marshall. It defended individual liberties and the constitutional rights of defendants, civil rights while ending segregation, broadened the separation of church and state, and paved the way for the right to a safe and legal abortion. In an era of uncertainty, the icons of the Court enabled us to feel safer.

It was also the era of crusading, heroic, radical attorneys who were in the vanguard of protecting the marginalized, voiceless and oppressed. They were exemplary champions of justice, intervening wherever there was government persecution. No client was too extreme or despised in the eyes of the public to deserve their defense. The most renowned was William Kunstler who defended the Chicago 8, those prosecuted in the American Indian Movement, prisoners in the Attica uprising, and numerous other high-profile cases. In 1966, out of the civil rights movement, Kunstler, together with radical lawyers Arthur Kinoy, and Mort Stavis founded the Center for Constitutional Rights (CCR).

Michael Ratner was among those crusading lawyers who came of age in that period. Michael Ratner was born into a large and loving Jewish immigrant family that settled in Cleveland and its suburbs. Not surprisingly education was highly valued and Michael’s Jewish background, including the history of Jewish oppression, helped inform the values he carried with him for a lifetime. The family was both observant and Zionist, and an early visit to Israel left a loving impression, an outlook that would change in his later years. Nor did he sustain the observance of his childhood. His father became successful in the building supply business, which enabled the family to move into the comfortable middle class. His family was by no means radical, but Michael admired his father’s contempt for discrimination, his support for arriving immigrants, and his generosity, experiences that set the foundations for his political values.

Michael went off to Brandeis University but fell into severe depression after his father’s early death, and he found himself dropping out of college. When he returned, his academic performance sufficiently improved to enable him to be admitted to Columbia Law School. Despite doing well, he dropped out as he did at Brandeis and found his first job doing research with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The Vietnam War was raging, and the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the pall of racial injustice hung in the air. A galvanizing moment in Michael’s move toward political radicalism occurred on April 30th, 1968 when he wandered onto the Columbia University campus. Students had occupied buildings demanding that the University cancel its contracts with federal agencies involved in the Vietnam War and it stop the construction of a gymnasium in Morningside Park. More than 1,000 cops invaded the campus, billy clubs swinging, and broke up the protest. Seven hundred students were arrested, there was blood everywhere. Michael was beaten and emerged a political radical.

Columbia filed disciplinary charges against the students, but the students legally fought back. Lawyers from the Center for Constitutional Rights defended the students along with attorneys from the National Lawyers Guild. Though they lost the case, the attention it drew caused Columbia to drop its plans for the gymnasium. This incident set a pattern Michael was to follow in his career. Legal cases on publicly contentious issues could be employed as a strategy to focus attention on them and thereby raise their profile in the public eye. Michael returned to Columbia Law and graduated first in his class.

After graduation, he clerked with Constance Baker Motley, the only Black woman federal judge in the United States. His work with the judge again put him in touch with Kunstler, Stavis, and Kinoy from whom he witnessed creative and aggressive lawyering, an approach he would appropriate as his own. Ratner admired Judge Motley but felt that her attachment to the legal system rendered her politics too limited. By contrast, he believed that change came from the streets.

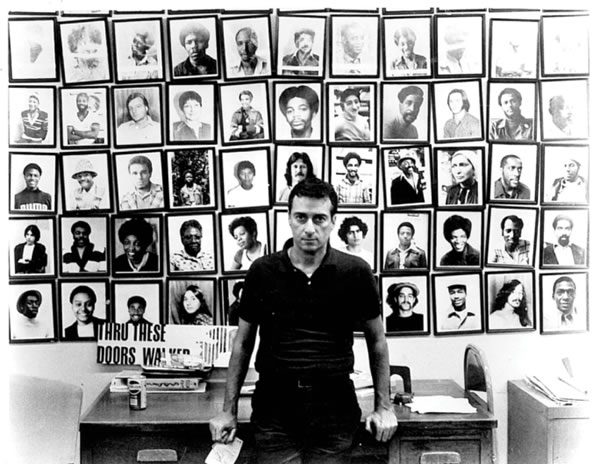

Michael Ratner’s tenure with Judge Motley ended in 1971 and he began his long career with the Center for Constitutional Rights. In its early years, it was a small organization with a large mission. Two days after his arrival, the uprising at Attica prison took place. With grievances of racism and physical and mental abuse, prisoners took several guards hostage and issued 28 demands. Bill Kunstler was asked by the prisoners to mediate. After a few days, Governor Rockefeller called for an assault on the prison. Thirty-two inmates and nine hostages had been killed. Contrary to initial reports, the guards were killed by the state. After retaking the prison, inmates were attacked and brutalized. Michael was sent by CCR to investigate. He became part of a legal team that drew up charges on behalf of the inmates against state officials responsible for the killing and brutality. The case was summarily dismissed. But the Attica tragedy imbued him with the conviction that radical injustice required a radical response, including filing lawsuits even if one is destined to lose.

The Center for Constitutional Rights was founded to defend activists in the Civil Rights Movement. As the Movement began to fade, it broadened its mandate to embrace international law claims and human rights, concepts that were new to Michael, but which he energetically pursued for the rest of his life.

His autobiography reads like a series of continuous legal actions on behalf of progressive and radical causes. Michael found himself defending Puerto Ricans who resisted being drafted into the military. He also defended Puerto Rican fishermen on the island of Vieques, part of which was a military base used as a bombing range. A colleague and others were also arrested for trespassing. Typical of Michael’s political commitments, he saw these legal initiatives as part of the larger struggle for Puerto Rican independence from the oppression of American colonialism. It was also a time when he traveled to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade and was duly impressed with the achievements of the Castro Revolution while critical of aspects, such as discrimination against gays, which stood against his values.

As the Reagan years began, Michael became the legal director of CCR. One early initiative involved him in legal action against the US travel ban to Cuba. The case went to the Supreme Court, and it was one of many Michael was to lose. But he shortly thereafter won a case in which the government sought to ban the distribution in the US of the Cuban newspaper Granma. More significant was Michael’s defense of a magazine titled CovertAction Information Bulletin which published articles about the CIA’s efforts to overthrow foreign governments, and the magazine named names.

This was a time of extraordinarily brutal warfare in Central America and Michael was fully invested in legal maneuvering to stop the administration’s support for wars in the region. He was involved in bringing a dozen laws suits to halt America’s military assistance to Central American dictators. The most promising was Crockett v. Reagan arguing that Congress had been denied the right to send 500 American soldiers to El Salvador as “trainers.” It failed as well but became a model for future litigation aimed at halting American military action. This was also the period in which a revolution in the tiny Caribbean island of Grenada was to install a socialist government with links to Cuba. A coup ensued, followed by an American invasion. Here too, Michael sought legal remedies to block the American takeover on the grounds that it clearly violated US law. By the time the suit was filed, the four-day war was over. CCR was deeply invested in the war in Nicaragua between the Sandinista government and the American-backed contras. It sent research teams to investigate the violence, and Michael was often on the scene placing himself in dangerous circumstances. Since the US was supporting the killing of Nicaraguan civilians and in some cases was directly responsible, Michael brought suit on behalf of Nicaraguan plaintiffs. As he noted,

“In addition to the Nicaraguan plaintiff’s testimony, our legal filing contained precise details about the U.S. funding of the contras, the locations of their training camps, in Honduras and Florida, as well as the source of the expended mortar shells we found, which were stamped ‘USA.'”

Again these cases failed, but they did not weaken Michael Ratner’s commitment to their importance. They became essential components in politicizing the injustices and pushing the cause forward, an outlook Michael referred to as “success without victory.”

A catalogue of the numerous law suits Michael Ratner championed does not itself reveal the work on the ground he laboriously engaged. He saw legal action as merely one strategy that was a component of the larger cause. He worked tirelessly with legions of organizers, liaised with other attorneys, many of them local, led tours of American officials, and got to know and worked with large numbers of advocates on the ground.

Many of Michael Ratner’s clients were relatively unknown. More illustrious were the figures and cases that commanded his attention toward the end of his career. The 9/11 terrorist attack and its ongoing aftermath became a focal point of Michael’s work. The hysteria and fear of the day resulted in an estimated 3,000 Muslims being detained. CCR came to their defense.

But defending the detainees held at Guantanamo was potentially far more controversial. No doubt, defending the most hated illuminated CCR’s and Ratner’s uncompromising commitment to basic American principles of liberty and justice. At one point, CCR was able to marshal more than 600 attorneys to work pro bono on behalf of hundreds of Guantanamo detainees. Michael assessed it as one of the great chapters in the struggle for fundamental rights in the United States.

But his most noteworthy case was the first of four brought before the Supreme Court defending the basic rights of Guantanamo detainees. The Bush administration denied them fundamental habeas corpus rights on the grounds that Guantanamo was not American territory. In Rasul v. Bush, Michael Ratner came before the Supreme Court arguing that anyone held anywhere in U.S. custody could not be deprived of a right that hearkened back to 1216 and the Magna Carta. This time he won in what the New York Times referred to as the most important civil rights case in 50 years. This was the first of four cases the Center brought before a conservative Supreme Court to safeguard the fundamental rights of those detained at Guantanamo, and under Michael Ratner’s leadership, they won all of them.

Bush’s War on Terror perpetrated human rights abuses on a massive scale. Among them was kidnapping purported terrorists, referred to as “extraordinary rendition,” and transporting them to one of eight “black sites” in hidden locations around the world. The most blatant abuse was the employment of torture that took place at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, Guantanamo, and at the aforementioned black sites. Under Bush, for the first time in our history, torture became a legal component of American policy though it violated domestic law, the military code of conduct, the Geneva Accords, and international law under the Convention Against Torture that the United States had ratified. Torture was given legal sanction through a series of memos developed by the Office of Legal Counsel, a sub-department of the Justice Department, and by Donald Rumsfeld, the Secretary of Defense.

Ratner, through the CCR, was intent on charging Donald Rumsfeld and nine others who orchestrated torture as war criminals. The strategy was to have them arrested and tried under the doctrine of universal jurisdiction, which allowed for the trial of anyone who had committed mass atrocities to be tried in any competent court anywhere. Such, needless to say, was a very bold initiative, but it had precedents, including a path-breaking case that the Center had earlier litigated and won. That case involved a young Paraguayan, Joelito Filartiga, who was tortured to death by officials in Paraguay under the longstanding dictatorship of Alfredo Stroessner. As it so happened, both relatives of Filartiga and his torturer were residing in New York at the same time. Filartiga’s torturer was bought to trial and convicted in what was a civil suit in a Brooklyn courtroom, though the crime has been committed in Paraguay.

Using the principle of universal jurisdiction, Michael worked with an activist German lawyer, Wolfgang Kolek, who had been involved in similar cases in Germany. In November 2004, Kolek filed a 160-page criminal complaint against Rumsfeld and the others on behalf of CCR and four Iraqi detainees who had been brutally tortured at Abu Ghraib. Not surprising, such cases are highly vulnerable to political dynamics and in February 2005, the complaint was dismissed by a German prosecutor, no doubt under pressure from the United States.

Though ostensibly chimerical, the suit against Donald Rumsfeld and other high-level American officials for war crimes drew much attention in Germany. It also has resulted in world leaders, who have been perpetrated major human rights abuses, being cautious as to where they travel. Germany has just recently convicted and imposed a life sentence on a Syrian torturer who committed his crimes in Syria in the extraordinarily brutal eleven-year civil war in that country employing universal jurisdiction as the approach. We can expect that the movement which the CCR and Michael Ratner initiated in modern times will expand its use and find a place among the various strategies to end impunity in the service of protecting human rights.

The first chapter of “Moving the Bar” narrates Michael’s work with and in defense of Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks, which involved Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden in a case still to be resolved. It was Michael Ratner’s final initiative before his death in 2016. Like all his work, it exemplified his principled commitments to justice and to truth. In a typical statement, he noted, “My experience has taught me that the truth has a way of coming out, even when the most powerful government on earth tries to crush it. Each time a whistleblower, a publisher, or a hacker, has been jailed, tortured, or driven to suicide, other truth-tellers, have come forward. And there will be many more.” It was a statement of conviction and faith, and Michael Ratner could well have been describing himself.

“Moving the Bar,” the story of a courageous, principled, and idealistic lawyer, is a compendium of legal cases, victims, horrendous abuses, crusading attorneys, judges, grassroots organizers, figures who were famous and ordinary folks. While centered around his work, Michael Ratner’s story is also very much a human one. Together with his relentless drive for justice, he lays out his vulnerabilities. Throughout the narrative, Michael Ratner is open about his doubts, his failures, and his feelings of insecurity and inadequacy before walking into the courtroom. He also cites his admiration for others, his warmth toward his friends, his love for his family, and his devotion to his children.

Today we would no doubt assess Michael Ratner as a product of an elite background. He had a stellar education and worked as a professor of law at NYU, Columbia, and Yale. Yet he sought to transcend his privilege by living his life outwardly in the service of those most oppressed and inspired by the vision of a just world.

Michael Ratner was socialized by his times, and we are now in a changed environment. But certain values and ideals are perennial. He stands as an inspiring model for those who choose to devote themselves to the cause of justice, and especially for women and men entering the legal profession who aspire to dedicate themselves beyond self-interest. On the personal side, when thinking of Michael Ratner, whom I had the pleasure to interview in years past, an insight attributed to William James I think is apt, “The great use of life is to spend it for something that will outlast it.” He certainly did.

Michael Ratner had written on a sheet of paper taped to the wall near his desk, the following four principles that guided his work as a radical lawyer. It sums up the career and the man. It read as follows:

1. Do not refuse to take a case just because it is long odds of winning in court.

2. Use cases to publicize a radical critique of US policy and to promote revolutionary transformation.

3. Combine legal work with political advocacy.

4. Love people.

I like that.