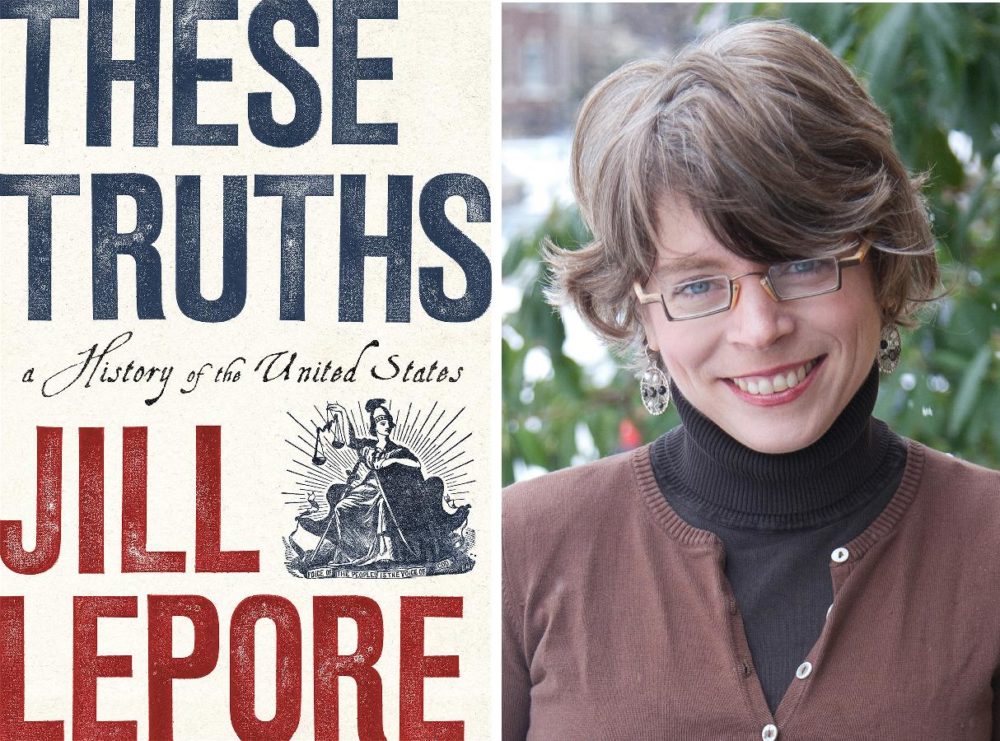

Jill Lepore’s one volume history of the United States These Truths is no less than a monumental, indeed magisterial, achievement. Her title, taken from the Declaration of Independence, is suggestive of the solidity of natural law. But the nation that was based on natural law principles was never secure nor certain. America has been a continuous process of contestation, contradiction and conflict, strife and the struggle for self-definition.

In her epilogue, she summarizes the theme that courses through her 900 pages of American history:

“The American experiment has not ended. A nation born in revolution will forever struggle in chaos. A nation founded on universal rights will wrestle against the forces of particularism. A nation that toppled a hierarchy of birth only to erect a hierarchy of wealth will never know tranquility. A nation of immigrants can never close its borders. And a nation born in contradiction, liberty in a land of slavery, sovereignty in a land of conquest, will fight forever, over the meaning of its history.”

Jill Lepore is a Harvard historian and a staff writer for The New Yorker. Her ability to unify facts and personalities, most well known, many not well known but illustrative of their time, together with defining movements in American history, is prodigious. Lepore’s style is captivating, and her language colorful and engaging. It kept me always eager to discover what came next. Though she underscores the novelty of the American experiment she doesn’t lapse into hagiography nor is she cynical, while never permitting the reader to escape the nation’s failures, especially its treatment of minorities.

In this regard it is clear that history is inevitably written through the lens of the present, and These Truth is most assuredly an historical narrative for our times. The passage cited above clearly renders that perspective. In our current moment of racial reawakening, I was struck by Lepore’s emphasis on slavery and the struggles of Black Americans as intimately woven into the American narrative.

Lepore’s repeated descriptions of relentless slave rebellions and Indian uprisings in the colonial period ensured they were not marginal to the colonists’ political and philosophical views as they strove to break free from English domination. The American colonies and the Caribbean islands were functionally an economic and political unit and rebellions of enslaved people were frequent and feared. The value at issue was freedom, and Lepore draws the intriguing observation that the motivation that inspired the revolutionaries to free themselves from British tyranny was not only the tyranny itself, but the example set be slaves and Indians to be free of the oppression foisted on them by the colonists. As she notes:

“Slavery does not exist outside of politics. Slavery is a form of politics, and slave rebellion a form of violent political dissent…In American history, the relationship between liberty and slavery is at once deep and dark: the threat of black rebellion gave a license to white political opposition. The American political tradition was forged by philosophers and statesmen, by printers and writers, and it was forged, too, by slaves”.

Slavery was continuously in the forefront of debate. Quakers forbade membership to slave owners and abolition was hotly debated in the colonial environment. Lepore observes that the adoption of the Declaration of Independence was a stunning rhetorical achievement, an act of extraordinary political courage. But is was also a colossal failure of political will, “in holding back the tide of opposition to slavery by ignoring it, for the sake of a union that in the end, could not and would not last.”

But the status of slavery by no means was the only division that characterized the American experiment from the beginning and throughout the nation’s history. Divisions and conflicts provide a major theme among many around which Lepore constructs her sprawling narrative.

Ratifying the Constitution generated rabid debates between federalists and anti-federalists; debates surrounding the powerful federal government versus the states, which continue to cleave the nation. Lepore notes the conflicts between those who supported greater democracy as exercised primarily at the state level and those skeptical of direct participation in government by the people. For many, democracy was a form of government to be spurned.

The battle between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, she notes, was between aristocracy and republicanism. The conflict between John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson was between republicanism and democracy, with democracy eventually prevailing as direct government increasingly shifted to the hands of the people. Jackson marked a shift in the presidency, He was the first candidate to actively campaign. He was also the first populist whose populism professed racial hierarchies and manifested the worst of populist tendencies. He waged ferocious campaigns against Native Americans and forcefully moved tribes from the their ancestral homes in a plan to move all Indians from the the southeast to lands in the west. According to Lepore, Jackson was “provincial and poorly educated” and he turned these characteristics and his lack of political experience into virtues.

There is an overlap between the emergence of populism and the religious awakening in the 1820s. At the time of the Revolution few Americans were church affiliated. With the Second Great Awakening, evangelical Christianity spread widely. Promoting the equality of souls, it spurred a democratizing effect that animated political culture. And since churches were greatly sustained by women it encouraged women’s engagement in political movements. In contrast to today’s fundamentalism, the evangelicalism of the day was active in the abolitionist movement and in promoting the interests of women, among them temperance, considered a progressive cause.

Lepore gives great weight to the role on the growth of technology and its impact on the political culture on in the early 19th century. We usually think of the Industrial Revolution emerging in the post-Civil War period, but she describes he development of steam power, the telegraph and the emergence of factories in the early decades of the century. These developments transformed the relations of men and women, workers to bosses, and a fervent belief in progress. It also spurred immigration, mostly of Germans and Irish and provoked nativist backlashes.

And there was always the issue of race. Lepore introduces Maria Stewart, a figure, who most likely does not appear in standard American history texts. A free Black from Boston, the author depicts her as reflecting a fusion of Christian revival and anti-slavery politics. Stewart caught the attention of the famed abolitionist, William Lloyd Garrison who took her on as a writer. Basing her arguments on scripture, she wrote and railed against slavery. Most interesting, was that in this early period, Stewart addressed mixed audiences of both women and men, Blacks and whites together.

In the antebellum years, Lepore stresses that America was a nation divided, slavery providing the major fault line. She amply discusses the role of Frederick Douglass, noting that Douglass was the most photographed personality of the period. In a way that perhaps presages the impact of the internet, Douglass believed that the new photographic technology was a powerful tool in proliferating the abolitionist cause. With compromises, debates, speeches and struggles, and John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry, Lepore depicts the 1850s as moving almost inevitable to the cataclysm of Civil War. When the War came, it was unprecedented. Typical of her prose, Lepore writes:

“The Civil War inaugurated a new kind of war, with giant armies wielding unstoppable machines, as if monsters with scales of steel had been let loose on the land to maul and maraud, and to eat even the innocent. When the war began, both sides expected it to be limited and brief. I instead it was vast and long, four brutal wretched years of misery never before seen.

In campaigns of singular ferocity, 2.1 million Northerners battled 800,000 Southerners in more than two hundred battles. More than 750,000 Americans died Twice as many died from disease as from wounds. They died in heaps; they were buried in pits.”

Perhaps because he has received voluminous treatment elsewhere, Lepore’s discussion of Abraham Lincoln is surprisingly limited. She focuses on his early years and the contrasts of his anti-slavery views with those of Stephen Douglas. As Lepore notes, Lincoln grounded his views in American history, the Constitution, noting also that the thought of Frederick Douglass was an important influence.

Emancipation renewed the debate as to what exactly was meant by the notion of “citizen.” Along with a host of contested issues, the role and scope of the Supreme Court, who was qualified to vote, how to count slaves, the privileges and entitlements that accrued to a “citizen” remained unclear for years after the Civil War.

Lepore provides ample discussion of the emergence of Jim Crow laws after Reconstruction, the emergence of the Gilded Age and the reforms that comprised the progressive era. There are conceptual discussions of the relationships between populism, progressiveness and liberalism, which clearly have their application to the present moment. She discusses at length Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal liberalism (and the exclusions of Blacks from many of its programs) as well as the emergence of conservative reactions that brought together businessmen with rural Americans who resisted government intervention in their lives.

Always interested in the influence of science and technology, Lepore gives emphasis to the role of polling, introduced in the 1930s, and how, in her analysis, it has served to skew the electorate and how polls have often proved woefully inaccurate. Perhaps presaging the coming of social media in molding opinion, Lepore provides fascinating discussion of the role played by radio and debates over its influence. It boosted evangelical religion by providing an outlet for radio preachers. Not only did millions tune into FDR’s fireside chats, but huge numbers were influenced by the the anti-New Deal and antisemitic diatribes of Father Charles Coughlin.

The Second World War, the post-War growth of the middle class, the McCarthy years and the Cold War and the Civil Rights eras, including internal divisions, all get ample treatment. The author is also equally keen in discussing more recent trends: the New Left, the Vietnam War, Nixon and Watergate. It is here that she sees the emergence of cynicism about truth itself, an epistemic tendency that has transmogrified to a degree that threatens democracy and societal cohesion to their core.

There is the rise of modern conservatism, in great measure a response to New Deal liberalism and the expansive role of government. Reaching its apogee in the laissez-faire, trickle down economics of Ronald Reagan, she finds contemporary judicial trends in the emergence of originalism adopted by conservative members of the Supreme Court, in response to the privacy rights enunciated in the Griswald case, allowing for the sale of contraception, and Roe v. Wade.

Lepore is again prescient in her treatment of identity politics, especially in its currents manifestations. She notes:

“By the 1980s, influenced by the psychology and popular culture of trauma, the Left had abandoned solidarity across difference in favor of the meditation on and expression of suffering, a politics of feeling and resentment, of self and sensitivity. The Right, if it didn’t describe itself as engaging in identity politics, adopted the same model: the NRA, notably, cultivated the resentments and grievances of white men, feeding in particular, both longstanding resentment of African-Americans and newly repurposed resentment of immigrants. Together both Left and Right adopted a politics and a cultural style animated by indictment and indignation.”

Jill Lepore ends her long narrative shortly after the election of Donald Trump. She ends a trifle too early to take in the full ravages of Trump’s destructive rampages, but clearly sees what is at stake:

“The election had nearly rent the nation in two. It had stoked fears, incited hatreds, and sown doubts about American leadership in the world and about the future of democracy itself. But remorse would wait for another day. And so would a remedy.”

Indeed.

Jill Lepore’s These Truths is an extraordinary achievement. In a single volume it incorporates political and social history, “great men” and lesser knowns who deserve recognition. It provides statistics (never excessively) photographs and wonderful, engaging, anecdotes to illustrate points that might otherwise be dry. But most of all, Jill Lepore is a realist. There is little vaunted heroism here: The figures are all recognizably human. Above all else Jill Lepore’s America is a complex story of contradictions and conflict, a nation that forever seeks to remake and define itself. The American narrative, our America, remains open and unfinished.

This is a history of America we all need and need now.