By Leader Joe Chuman

Originally published on his Substack, Beyond Appearances.

Note: On Sunday, January 9th, I interviewed Professor Nadine Strossen on her book which I review below. It was an engaging experience with a leading expert in the field of civil liberties and First Amendment rights. For those interested in the interview, it can be found on YouTube at the link above. JC

________________

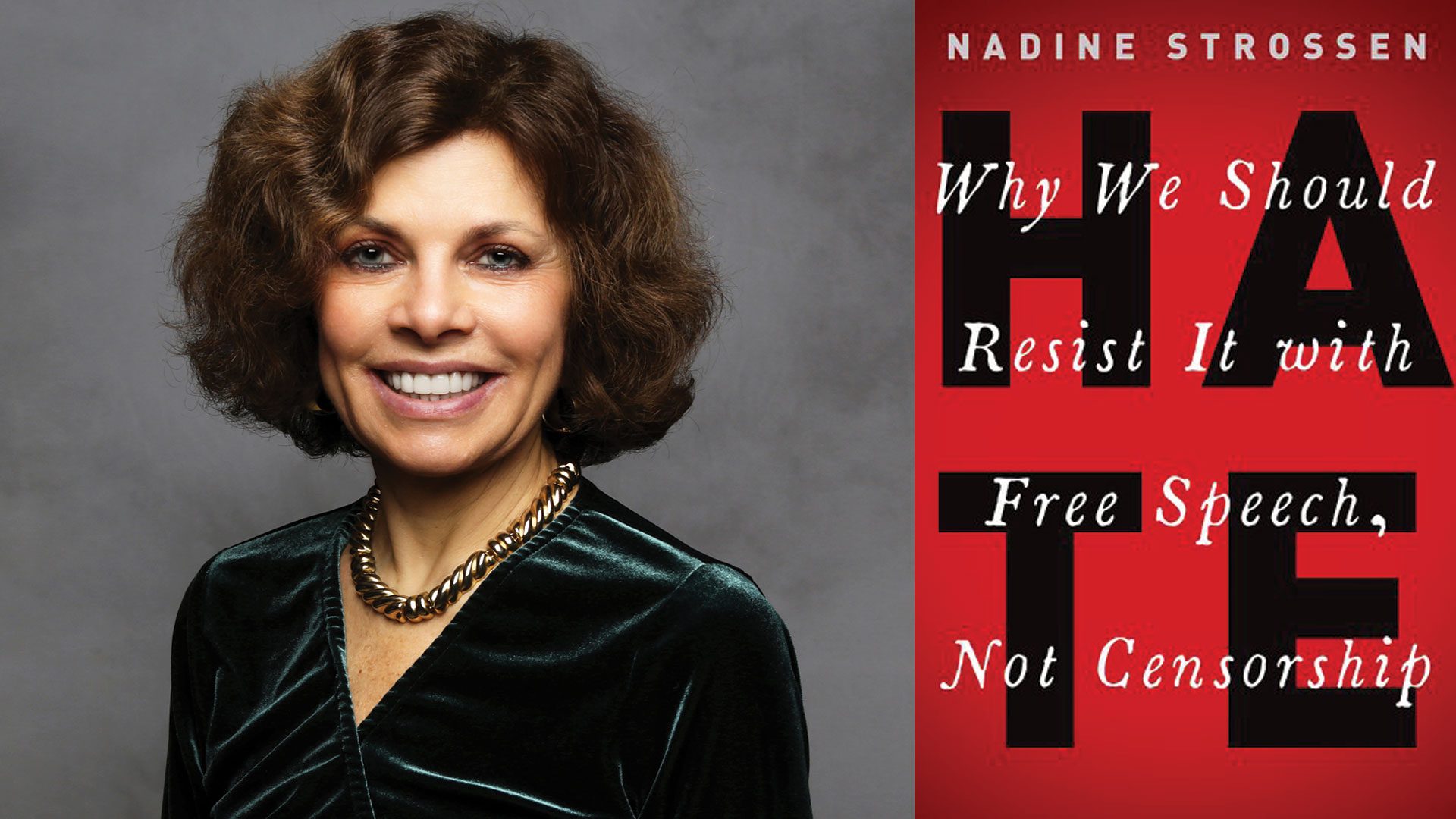

Nadine Strossen, the former president of the national American Civil Liberties Union, has written a book on hate speech as important as it is timely. In the midst of our current turbulent climate resurgent with hate groups and militias brandishing the mantras of white supremacy, writing this book is also an act of courage. The espousing of “hate speech” directed at minorities, immigrants, political adversaries, and others may tempt some to want to see laws enacted that are intended to prohibit and rein it in, but Strossen’s book presents a series of detailed and compelling arguments as to why we should not succumb to that temptation.

It was my privilege to recently interview Professor Strossen on Hate: Why We Should Resist It With Free Speech, Not Censorship as one in an ongoing series of discussions with noted authors under the aegis of the Puffin Cultural Forum in Teaneck, New Jersey. Strossen, who is a professor at New York Law School, is a sharply articulate and deeply informed defender of the First Amendment. Her book is tightly argued, going beyond legal issues to embrace relevant social science, psychology, and judicial history. As a student of human rights, I found it of great interest that Professor Strossen ventures outside the American context to reference the international human rights regime as well as the fate of hate speech laws in foreign countries.

It is evident that Strossen’s thesis is not a defense of hate speech but of the right to hate speech, and she reminded me early in our interview that the only verb in the book’s title is “resist.” As she makes amply clear in her text, the allowance of hate speech is ironically one of the strategies that is necessary in the struggle to resist it.

A major share of her argument is that the laws to preemptively prohibit the utterance of hate, whether targeted at individuals or groups, have no place in a free and democratic society, but actually exacerbate the very conditions they are intended to suppress.

The prevailing principle, long championed by the ACLU, is that under the First Amendment, the government must remain neutral with regard to the content of speech. It is simply not the government’s role to dictate what you or I may express in speech or writing. But the right to free speech is not absolute, and a strength of Strossen’s presentation is that it is richly detailed and nuanced in elucidating the complexities of hate speech laws, their consequences, and ways to counteract hate.

Strossen makes eminently clear that speech is by no means otiose nor powerless. Words inform values and attitudes, and they can and do motivate action for good and ill. Some hate speech in fact is prohibited and the Supreme Court is the ultimate arbiter with regard to setting boundaries for which speech, in narrow circumstances, is justifiably unlawful. These boundaries have changed over time. She notes such a change: “Until the second half of the twentieth century, the Supreme Court enforced the deferential ‘bad tendency’ standard to permit government to suppress speech whenever it maintained that the speech might cause harm at some future point.” For example, as a result of decisions rendered in 1919, the Court upheld criminal convictions for speech opposing American involvement in World War I, on the grounds that it might encourage draft resistance, and the conviction of Socialist Party leader, Eugene V. Debs was upheld for giving a wartime speech opposing the draft. But this standard subsequently changed primarily through decisions of Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes and Louis Brandeis, who confirmed government neutrality, expounding that the First Amendment bars the government from suppressing “opinions we loathe.” It is this standard that we retain and which Strossen strenuously defends.

Among the narrow circumstances in which hate speech remains prohibited is “the emergency principle.” These circumstances are all context-specific. Examples include speech involving “true threats” in which the speaker seriously intends to commit an unlawful act of violence against an individual or a group and the object of that speech has a reasonable fear that the assault will occur. Context, again, is crucial. So if a coven of KKK members burns a cross unseen by others, this expression does not meet the emergency test prohibition. But burning a cross on the lawn of an African-American assuredly would and is illegal. Speech that intentionally incites imminent violence, or ensures that violence is likely to occur is also barred. Moreover, harassment is not protected, including persistent harassment in the workplace that creates an abusive work environment. On the other hand, generalized threatening words construed to be politically hyperbolic or rhetorical, are legally permissible.

However, with obvious pride in what she sees as the common sense of the American tradition, she underscores the broad scope of free speech. To make the point, Strossen frequently states that the emergency test does not bar speech that is “disturbing, disfavored, and feared,” the last implying that the message might indeed contribute to potentially harmful conduct at some future time. But, again, fear of potential harm is not sufficient to outlaw such speech.

The reality that some speech is felt as disturbing is especially relevant because it touches upon an often encountered source of conflict that has become increasingly familiar. Both Nadine Strossen, who is a professor of law at New York Law School, and the current reviewer, who teaches human rights in the academy, are aware of how fraught speech has become on college campuses. The classroom, which should be the premier venue for the debate of ideas, including ideas that are controversial, has often been turned into an arena wherein previously engaged and lively discussion now suffers a chilling effect. We see the introduction of hate speech codes on campus. But beyond such codes censorship extends further. She notes,

“In at least some circumstances current campus censorship threatens even more speech than the invalidated hate speech codes of the past. For example, some institutions have gone so far as to prohibit ideas that some students may find “unwelcome” or make them “uncomfortable.” “…today’s capacious concept of hate speech is often understood as encompassing the expression of any idea that some students find objectionable.”

“Even beyond official suppression, many public colleges and universities have experienced self-censorship among students and faculty about sensitive, controversial topics that urgently call for candid, vigorous debate and discussion. Given the adverse consequences at stake, there is widespread fear of being accused of ‘hate speech,’ or even saying something that makes someone ‘uncomfortable,’ which is a damning indictment in the current campus climate.”

No doubt much of the discomfort relates to discussion around race and gender, and many professors sense that walking into the classroom today places them in a fraught environment. It is at this point that Strossen moves from law to social science to defend the notion that the damage done by disquieting speech is often misplaced.

She does not deny that hate speech sometimes does contribute to psychic and emotional harm’ to some people it disparages. Arguments are made that because of structural power inequities with deep historical reach, institutional racism being the most salient, such harm is palpable and offensive speech should be curtailed. But these circumstances entail a great deal of nuance and variation. Moreover, she asserts that more empirical research needs to be done on the real effects of disturbing speech on campus. Clearly, she believes that the negative harms have been overstated. Invoking social scientists, she notes,

“…experts recognize that ‘there are wide individual differences regarding what constitutes a ‘hateful message,’ and that ‘what speech is considered harmful depends critically on situational variables,’ including bystanders’ reactions, the message’s perceived intent, the relationship between the speaker and the listener, the topic of discussion, the location of the conversation, the language used, the speaker’s and listener’s body language, and the tone of voice.’” Studies she invokes indicate that different listeners had different responses to hate speech. In response to disturbing speech on campuses and elsewhere, her thesis counsels a broad range of responses from shoring up personal resilience to relevant education and to what she refers to as “counterspeech.”

When it comes to racist speech, Strossen invokes a significant number of Black leaders including – Thurgood Marshall, John Lewis, Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Eleanor Holmes Norton, and the NAACP – as opposing hate speech laws, recognizing that access to free speech has been among the most potent tools in the struggle for social justice and minority rights.

This provides a good point to segue into a central argument that hate speech laws, though initially emotionally satisfying, in application fail to curtail the very hatred they are intended to suppress and in some instances actually amplify a hateful environment. Moreover, such laws not infrequently target the very disenfranchised groups they are meant to protect. In short, hate speech laws are dysfunctional.

Nadine Strossen draws amply from the international context, especially from Europe and Canada, to illustrate the problematic consequences of such laws. A central problem is that hate speech laws are notoriously vague and therefore impossible to apply. She notes the Canadian Supreme Court’s efforts at interpreting hatred in laws that punish speech ‘that is likely to expose’ people to ‘hatred or contempt:’ ‘unusually strong and deep-felt emotions of detestation, calumny and vilification’ and ‘enmity and extreme ill-will…which goes beyond mere disdain or dislike.’ To make her point, Stroessen asks “If you were a juror, would you be able to distinguish between speech that conveys ‘disdain,’ which is not punishable and speech that conveys, ‘detestation’ or vilification,’ which is?”

In the American context, she cites an incident in which students at Harvard hung a Confederate flag from their dormitory windows, in obvious defiance of campus hate speech codes. In response to the Confederate flag and to expose its racism, other students hung swastikas from their windows. She asks, “should the swastikas count as “hate speech” or as anti-”hate speech?” She concludes, “…’hate speech’ is irreducibly riddled with ambiguity, conflicts and confusion.” “…I have done my best to track down and read every ‘hate speech’ law that has been enacted or proposed, and have yet to encounter one that avoids the serious flaws that I have identified.”

A further argument in opposition to hate speech laws are that they can ricochet to target the very vulnerable groups they are meant to protect. Black Lives Matters has been attacked as fomenting hate speech and if such laws existed there would be efforts at silencing the movement. In the current political climate such concerns are by no means remote. The counter-productive nature of hate speech laws was noted by columnist Glenn Greenwald when he wrote, “ Nothing strengthens hate groups more than censoring them, as it turns them into free speech martyrs, feeds their sense of grievance and forces them to seek out more destructive means of activism…Conversely as the aftermath of Charlottesville has proved, nothing exposes the evil of such groups, and this weakens them, like letting them show their true nature.”

A more extensive review would require a probing critique of the role of the internet and social media and their relations to promoting information that either sustains free speech and democracy or undermines them. The First Amendment, of course, pertains solely to government and public entities. Social media platforms are private enterprises and at this point are free to regulate speech however they choose. But it is Strossen’s view and that of many others, though not bound by the free speech mandates of the First Amendment, social media, like colleges and universities, should abide by its norms.

The extraordinary power and scope as such entities as Facebook and Twitter and other social media as conduits of information would ostensibly render that conclusion apposite. Strossen sees similar problems in banning hate speech on social media as she does with government, and she seems to be opposed to regulation.

While this debate goes beyond my personal expertise, my sense is that the issue requires a great deal of continued research and public debate. Social media, which initially presented itself as an unquestioned boon to the expansion of the marketplace of ideas, has arguably been transformed into a far more complex and conflicted reality. Professor Strossen points to the extraordinary capacity of social media to bring people together to organize for progressive social change. This is no doubt true. But critics point likewise to their appeal to impulse and often negative emotions in relentless pursuit of profits, their capacity to algorithmically feed back to people what they want to hear and thus reconfirm their biases, as well as their ability to silo hatred. Whether these gargantuan technologies enhance democracy or undermine it is not compellingly clear and I believe still an open question.

But what is clear to my mind, and as Nadine Strossen so compellingly demonstrates, is that when it comes to censoring hate speech the cure is far worse than the disease. In place of hate speech laws, she advocates counterspeech, which can take many forms. Among these approaches is speech that aims to refute hateful ideas, broader, pro-active education initiatives, and programs to empower disparaged peoples. Such approaches go beyond speech alone, but require programs to bring people together and to nurture values that will create a more inclusive society.

In my personal engagement with Nadine Strossen I encountered a scholar and activist, who is not only deeply informed on the fundamentals of freedom, but in our challenging times remains optimistic as to how far we have progressed, implying that a more benign future lies ahead. I found our encounter a source of needed inspiration. Readers will find Hate: Why We Should Resist It With Free Speech, Not Censorship a powerful and necessary defense of a cornerstone of our democracy and how to keep it.